Can parliamentary success be measured?

It’s hard to say what makes a good or “successful” representative without being simplistic. Indeed, there are many different ways to be an elected representative. One can be active in drafting legislation, be involved in their constituency, be a leading opposition figure, or control the government in a discreet but powerful way. One can also, though less obviously, use parliament to build a career – whether by raising one’s public profile, specializing, or networking. What’s more, not all MPs have the same opportunities. Majority MPs have different options and constraints than minority MPs.

It is therefore easy to understand why parliamentarians and parliamentary experts are so critical of the rankings that regularly appear in the media. While it would be illusory to find a single indicator of activity or success, we can try to show the role played by parliamentarians, a fruitful avenue already pursued by various researchers. In order to produce a precise description of parliamentary activity, I relied on my knowledge of the field, on that of various actors interviewed during the survey, and on the existing literature. Three types of variables have been collected. Each refers to a form of involvement in parliamentary activity that has been well documented in other works.

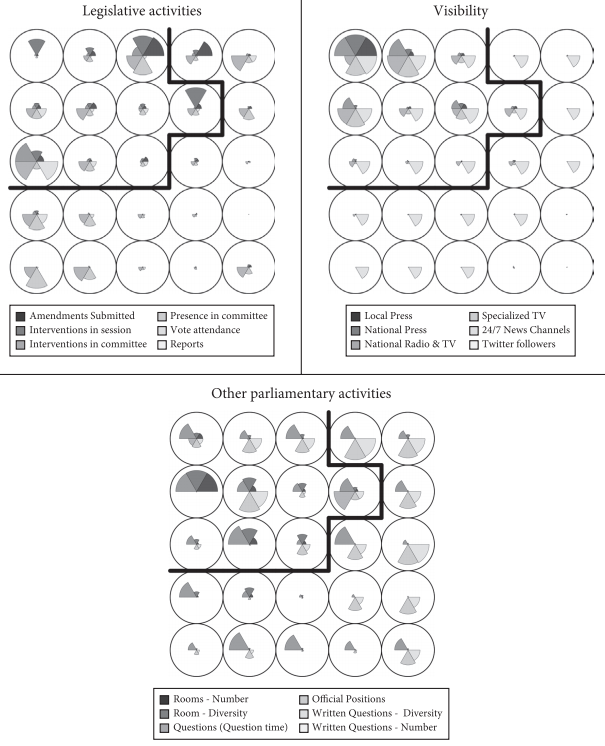

- The first brings together a set of indicators that capture the contribution of elected representatives to the production of legislation and the control of government.

- Another set tries to capture the media visibility of elected representatives, in its volume and its forms. To this end, I have collected the invitations of MPs in various audiovisual media, as well as in national and local daily newspapers, and their presence on Twitter.

- Finally, a final set of parliamentary activities was included to capture certain aspects of the mandate. Written questions, room reservations, parliamentary events, etc. remind us that in parliament one is not only a legislator. One can also build a reputation as an expert, and all activities cannot be analyzed without capturing the work of meetings and coalition building.

Making Sense of Data Using AI

To organize this mass of data, I turned to a statistical learning method of dimensionality reduction called self-organizing maps (SOM). The algorithm is a relatively old type of artificial neural network, having been invented in the early 1980s. Designed to simplify and visualize complex data sets, it has been used in many theoretical and applied fields, but rarely in the social sciences. However, it is extremely useful for a common task in these disciplines: synthesizing information contained in a multidimensional space.

The algorithm brings together people with similar practices. It places members with similar profiles in the same cell and separates those who are far apart. In other words, it aims to bring together MPs with relatively similar profiles in adjacent cells on the map, and MPs with different profiles in distant cells. Once the calculations are complete, the result is a simplified graphical representation of the dataset, which, although flattened to two dimensions, retains some of its essential properties.

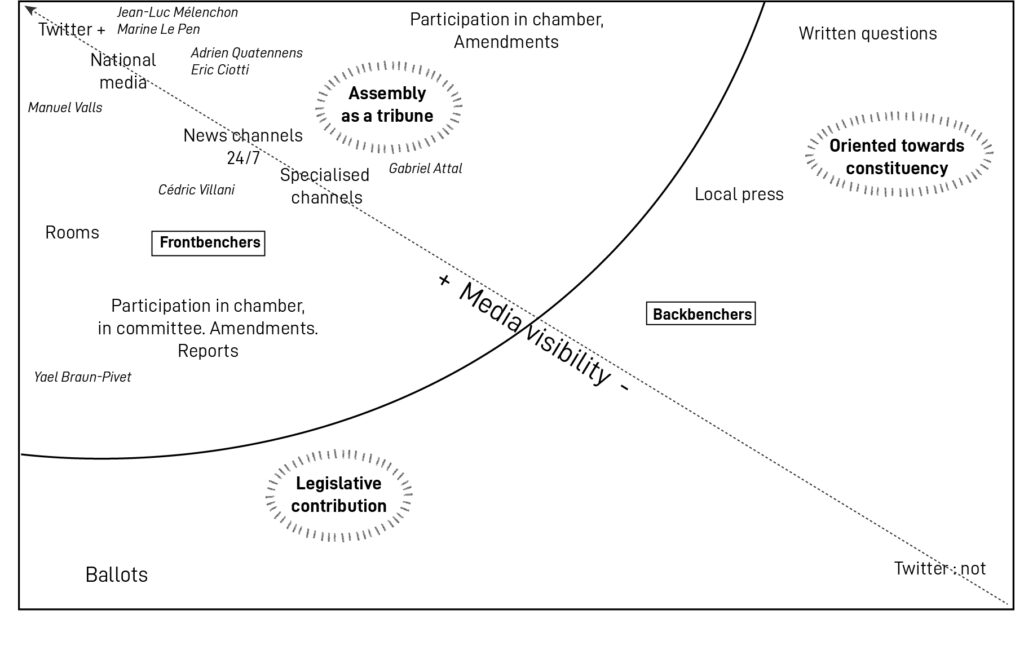

The figure below, created with aweSOM (a software developed by J. Boelaert), positions the MPs according to the different activities they were involved in during the first year of their mandate (June 2017-July 2018). We can see that in the north-eastern quadrant are all the political leaders and that around them are emerging profiles of leading MPs, but with different investments.

The graph, a representation of power and practice in parliament, is explained in details in chapter 3. But one can already that Gabriel Attal, the French Prime Minister at the time of the release of the book (Jan 2024), was already visible on this map in 2017 as an up-and-coming politician. More on this, and on his typical career path for France, in the book.

Controlling for other factors

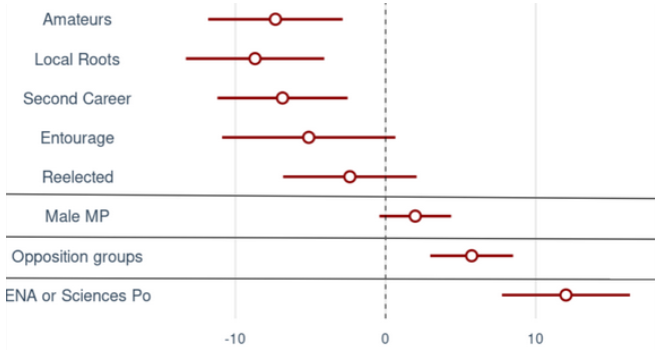

While these results tend to show that most amateurs were relegated to secondary roles, we still need to determine whether this was due to their lack of experience or to other factors. To do this, I ran parametric regressions to control for these other variables.

The one below is a regression on PC1, the first axis of a PCA on the same data, and a rough estimate of overall parliamentary success. It is regressed on several factors, including political career, gender, party affiliation (majority/opposition), and education. Here, as in other regressions, political careers seem to play a role – net of other variables.

The effects are sometimes barely significant due to the small size of certain groups, but they all point in the same direction.

Regression on PC1